Sophie Pierce (Member no: 132)

A Quoit Quest

I sat on a nearby stone, enjoying being in the presence of this moody megalith, looking out to sea, and thinking about a coastal walk earlier in the day

Down in Zennor for the weekend, to try and banish the January blues, Alex and I decided to go questing for quoits. In this part of Cornwall – West Penwith – a gloriously rugged and mystical place, quoits spring up from the ground everywhere. There are eight, in various states of disrepair, within an area of about 15 square miles between Zennor and St Just, which makes you wonder how many there were originally. Elsewhere in the country they’re called cromlechs, portal tombs or dolmens - a word derived from the Cornish word tolmen, a holed stone, like nearby Men-An-Tol. Quoit is a beautiful word though, probably from the French for silent or speechless, creating an image of a mouth of stone that makes no sound (fun fact: quoit is Aussie slang for buttocks).

Unfortunately, we’d chosen the weekend of Storm Ingrid, which ripped down piers and caused widespread havoc. On the Saturday the weather was so awful we spent most of it mooching around the shops in St Ives. But on the Sunday, it was the calm after the storm: a beautiful sunny day with little wind, perfect for stone-bothering.

Quoits are among the earliest megalithic monuments, built by our Neolithic ancestors around 4000 years ago. They generally consist of a massive capstone resting on stone pillars. It’s thought they were burial places; some archaeologists suggest they would have originally been covered with earth, creating a giant mound, but others suggest that these mighty stone structures were often uncovered, made to be seen from afar.

As for their use the Cornish Ancient Sites website says: “…it would be a mistake to think of these monuments simply as 'burial chambers'. The bone evidence from cromlechs in other places indicates that the disarticulated bones of a number of individuals may have been placed inside, and from time to time some bones were removed and were replaced by others. We may perhaps rather think of these sites as places where the tribe (or the shamans of the tribe) would go to consult with the spirits of their dead ancestors in trance journeys and altered states of consciousness. “

We set off from Zennor on the coast road towards St Ives, a vast expanse of bright sea to our right, and, on the left, inland, hills topped with the Carns, tor-like formations, reminding us of our home on Dartmoor. This uncanny feeling made sense though as we had been following the flowing subterranean granite down the spine of the Westcountry as it sporadically bursts upwards through the ground, starting high on Dartmoor and ending in the drowned stones of Scilly.

Our first target was Chun Quoit, reportedly the best preserved in the area. We parked on the road by the wonderfully named Woon Gumpus common and could already see the quoit, a squat stone toadstool clearly visible on the ridge in the distance.

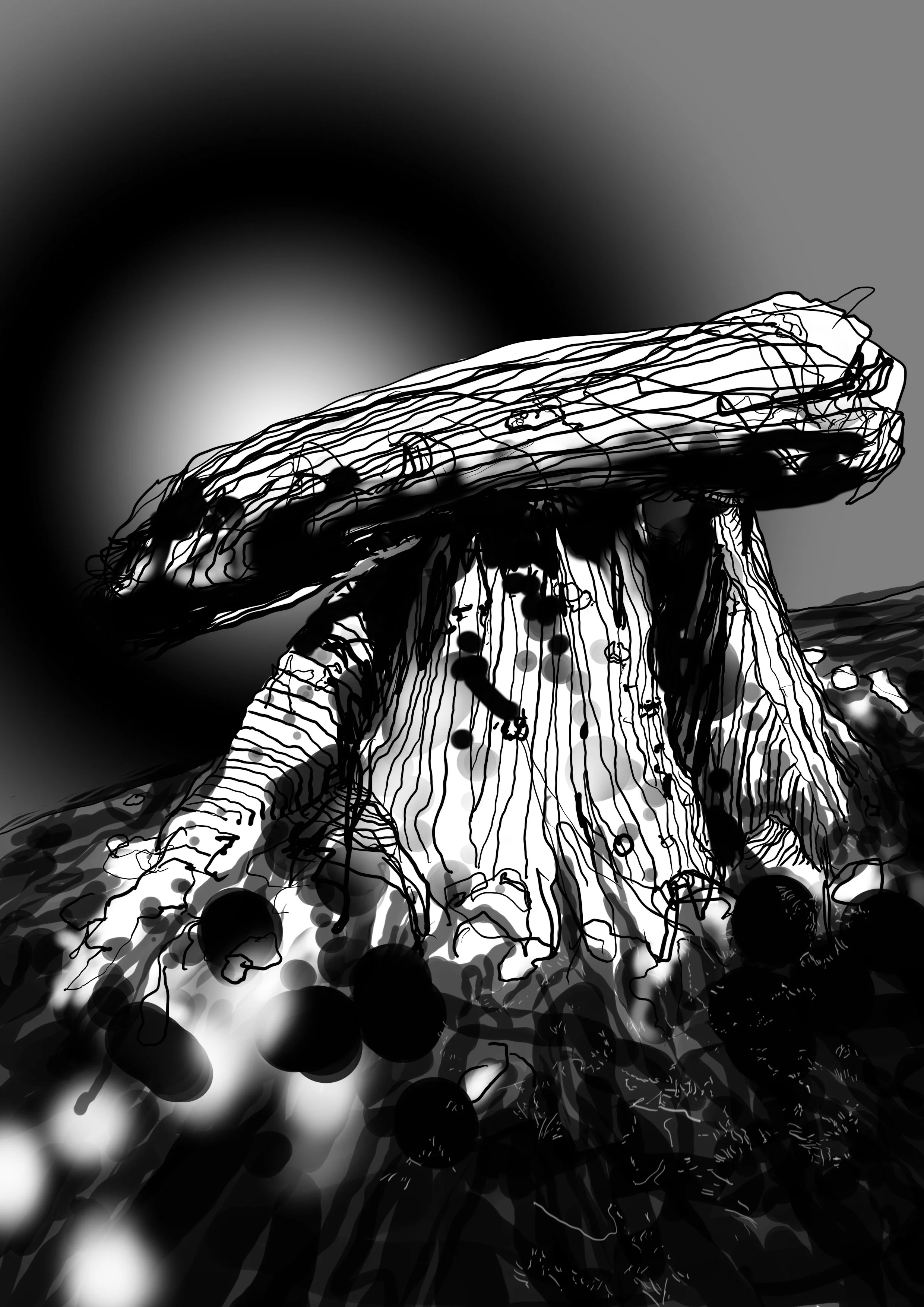

After a walk of about 20 minutes, across sodden moorland interspersed with enormous puddles full of frogspawn, we arrived at the site. Chun Quoit is in an exhilarating position, with expansive views of both the turbulent sea and Carn Kenidjack, a brooding tor to its south west. Up close the quoit looked even more like a mushroom, a large Penny Bun perhaps, its fleshy capstone leaning down on one side, the stones of its stem bunched together in the centre, swelling outwards at the bottom, its rhizomes reaching downwards and reaching back towards Dartmoor and out to the blessed isles in the inky distance.

I sat on a nearby stone, enjoying being in the presence of this moody megalith, looking out to sea, and thinking about a coastal walk earlier in the day, where we’d come across an extraordinary outcrop on the cliffs, with a rock balanced between two larger ones, a natural dolmen. It is known as Witches’ Rock, and creates a window to the sea beyond. There is an echo of this at Chun Quoit, where the uprights allow glimpses of the sea. We passed the time of day with a man out walking his mud-spattered sprocker dog. A couple of other stone-botherers wandered up to take photographs with their Leica camera.

As we walked back to the car, we noticed an angular construction in the distance, like a space ship. This turned out to be an air traffic control station, presumably for tiny Land’s End Airport; a curiously resonant sight, making us think of the skies above and the people looking down on us, ancient ancestors and airline passengers alike.

The next stop was Lanyon Quoit, a very different proposition to Chun Quoit. At first glance, it looked like a miniature component of Stonehenge, its large, regular capstone beautifully horizontal on top of elegant supporting stones, much more ethereal looking than Chun, more delicate fungus than earthy mushroom. Being very near the road, this is a much-photographed monument, but its current looks owe much to being heavily restored, having collapsed in a storm in 1815. Like Chun, it has wonderful views, but the sea is not such a dominant part of its surroundings. It felt like it was more connected to the ground and we were more connected to the land because of it. We walked under it and around it, inevitably wondering what this place meant to the people who built it, and why it still has such power, thousands of years later.